Sewage water discharged in the Senne and the canal

In the near future, the Brussels River Senne will be uncovered in Maximilian Park. Together, with the expansion of the park, this will create a place where people can be close to nature and water in the city. This is also a symbolic action to break with the mistakes of the past when the Senne was used as an open-air sewer and had to be hidden underground 150 years ago. But is the Senne ready to be uncovered in the city centre today? Is it free of sewage discharges? The answer is no, the Senne and the canal are polluted with sewage water through the sewer overflows all year round on rainy days. These discharges are a major environmental problem affecting the ecosystem, lowering oxygen levels in the water and injecting plastic waste and trillions of microplastics into nature. Moreover, it can also cause health problems for people. See below the number of overflows in recent years.

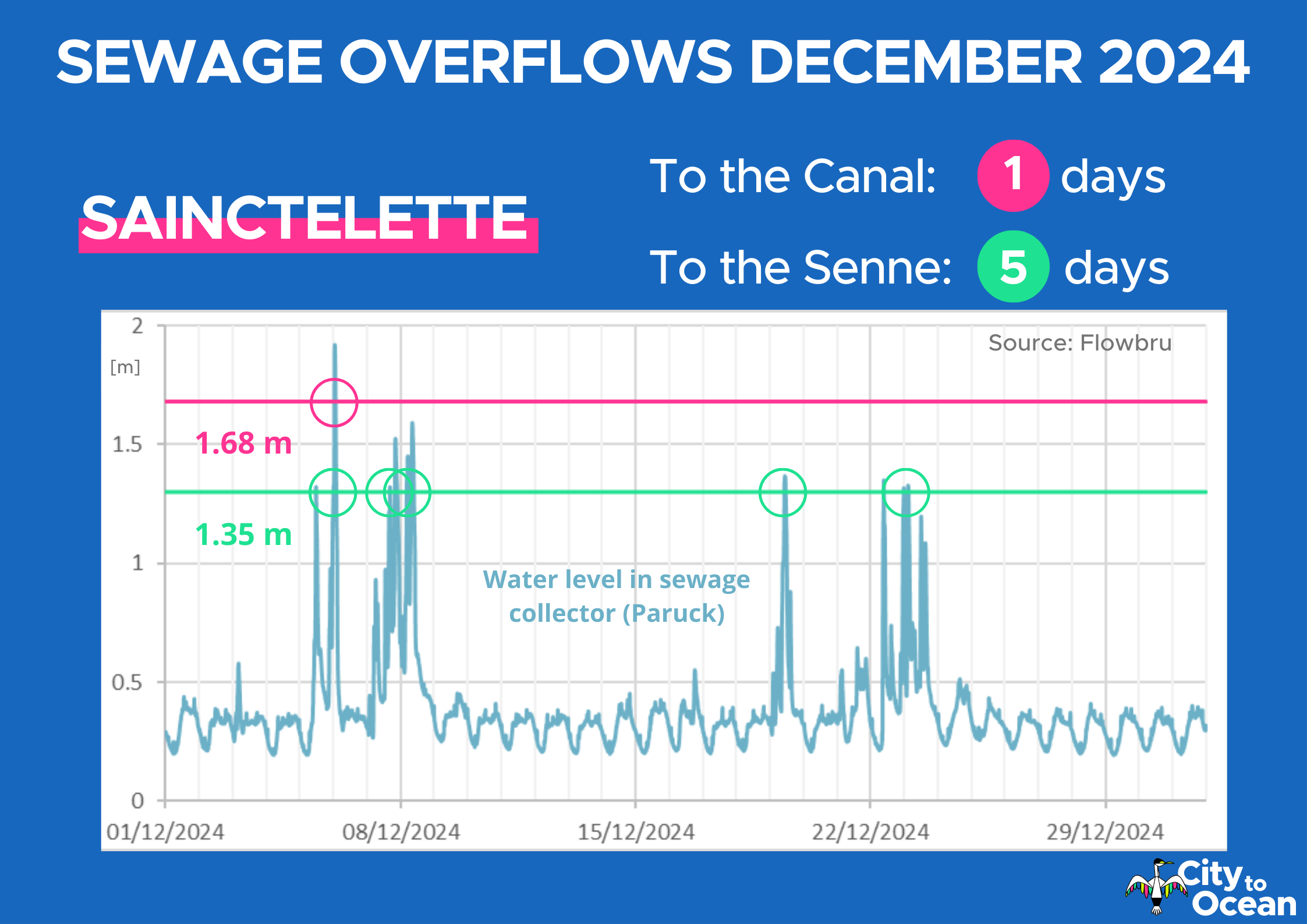

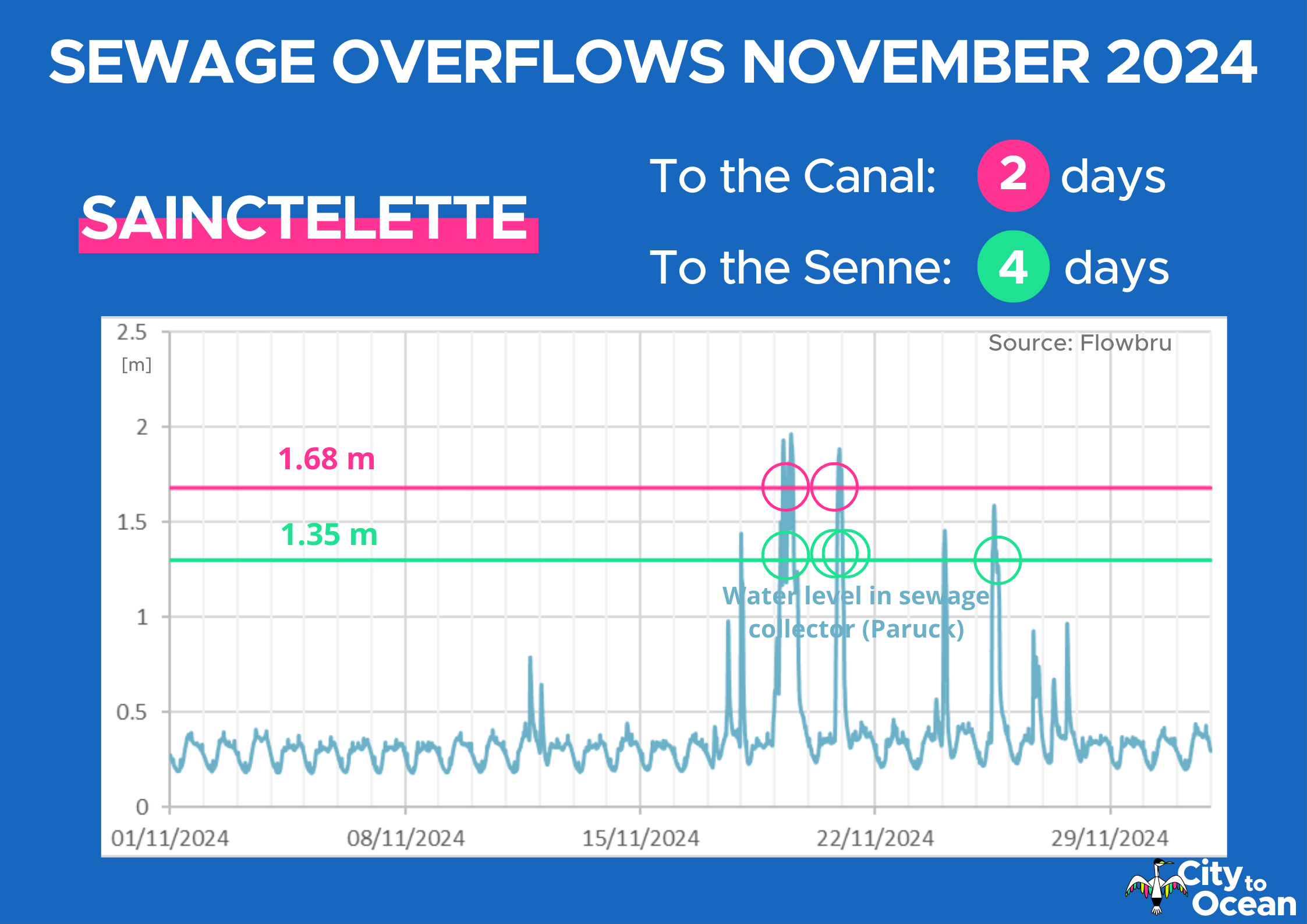

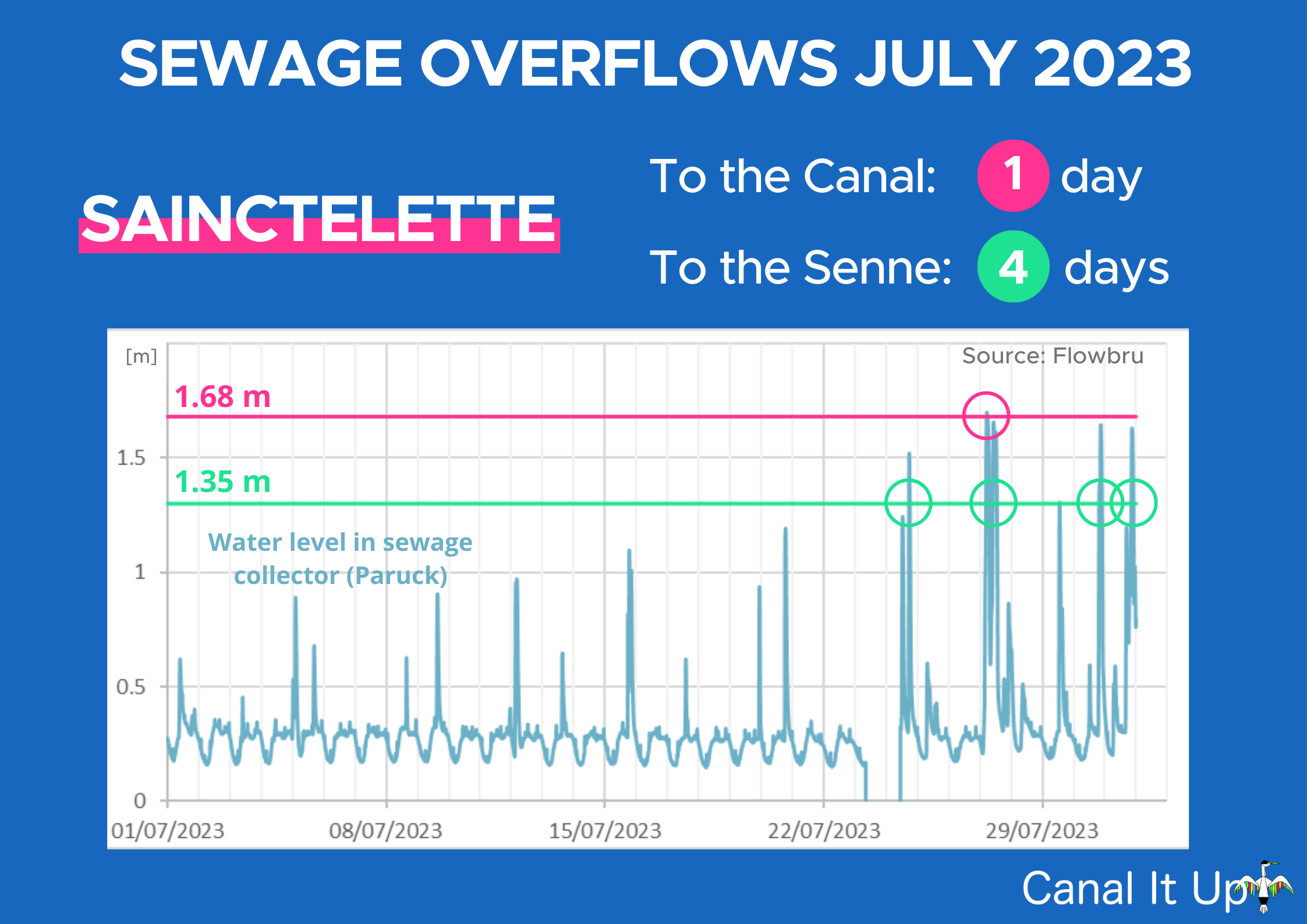

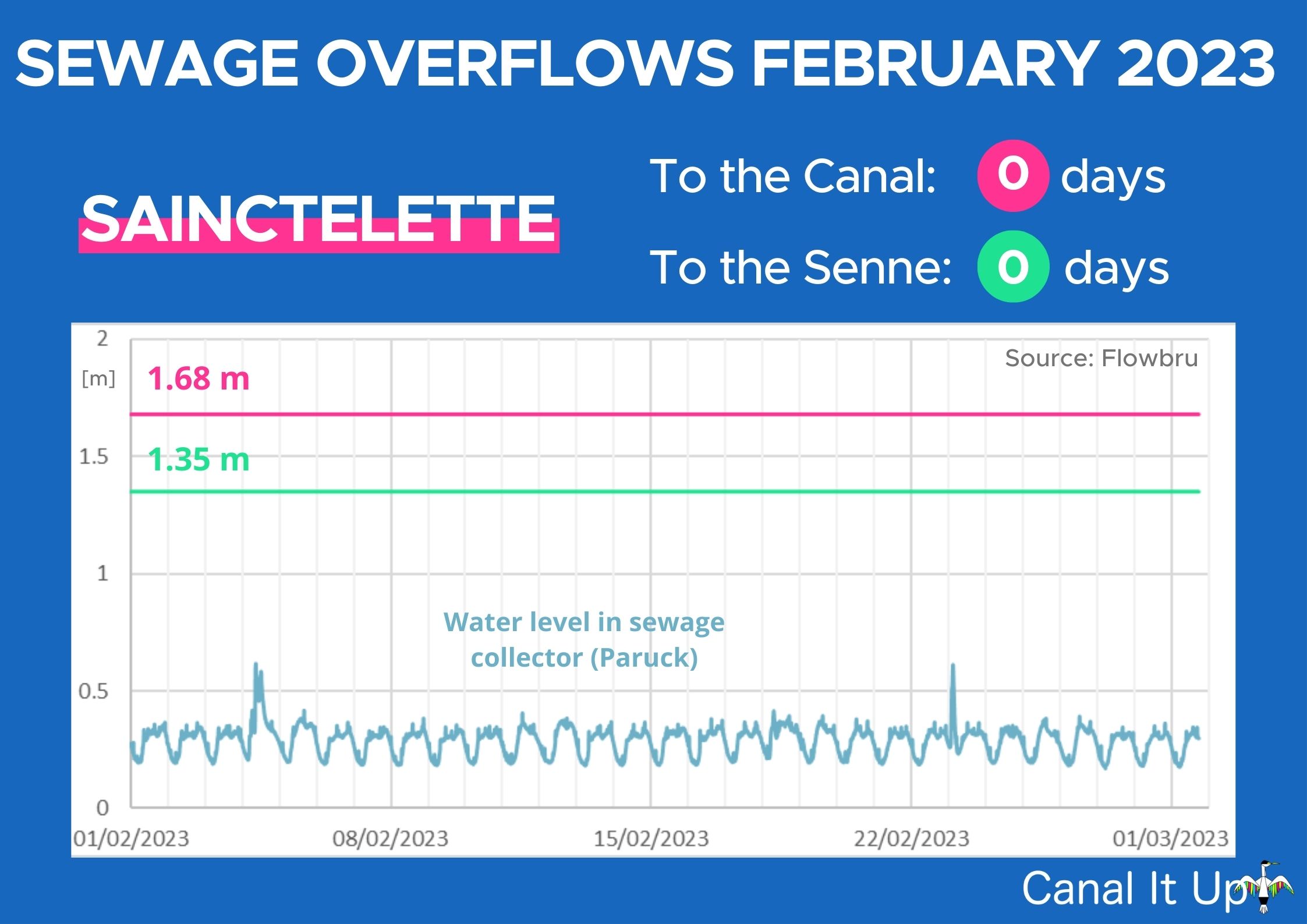

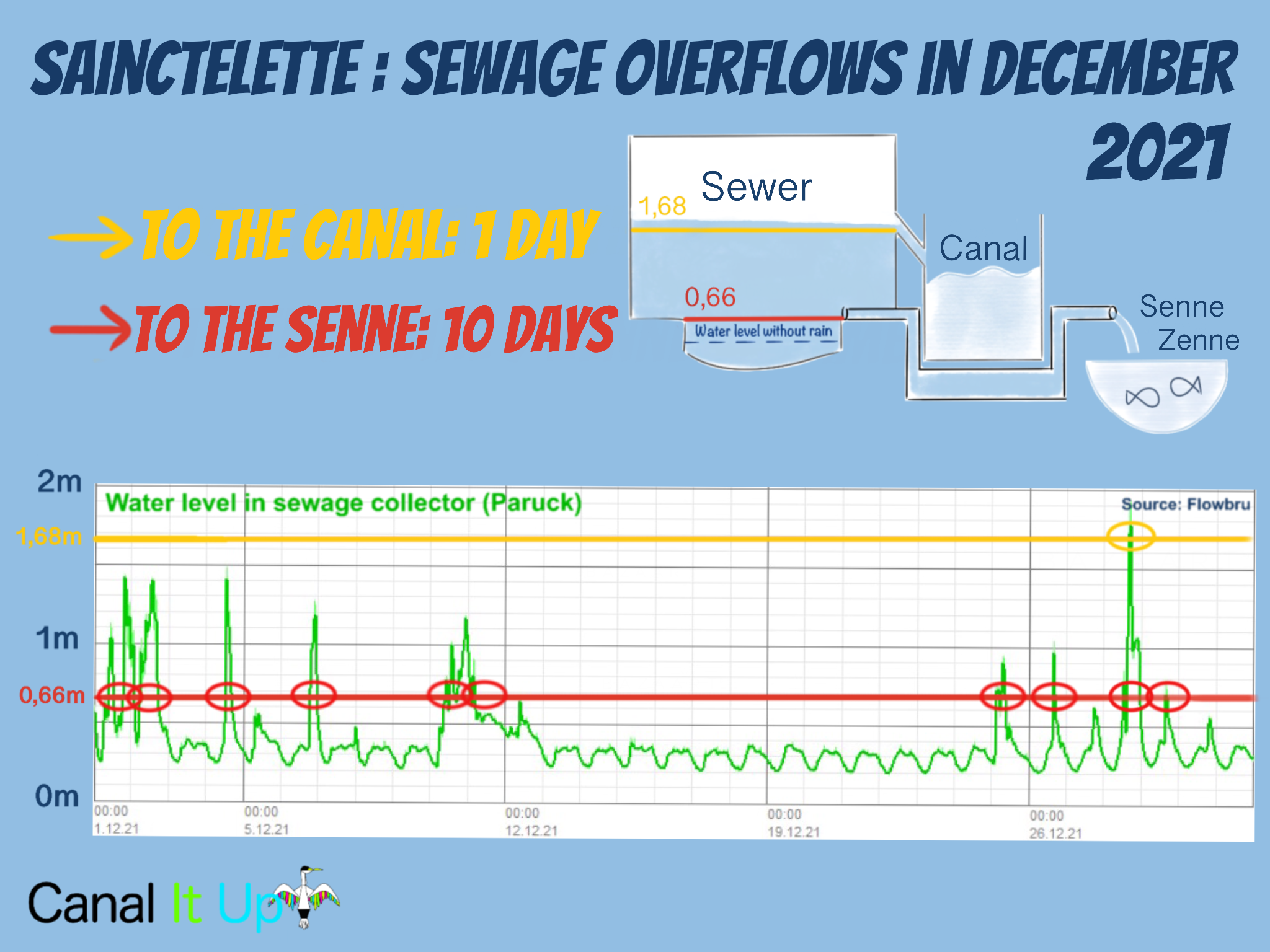

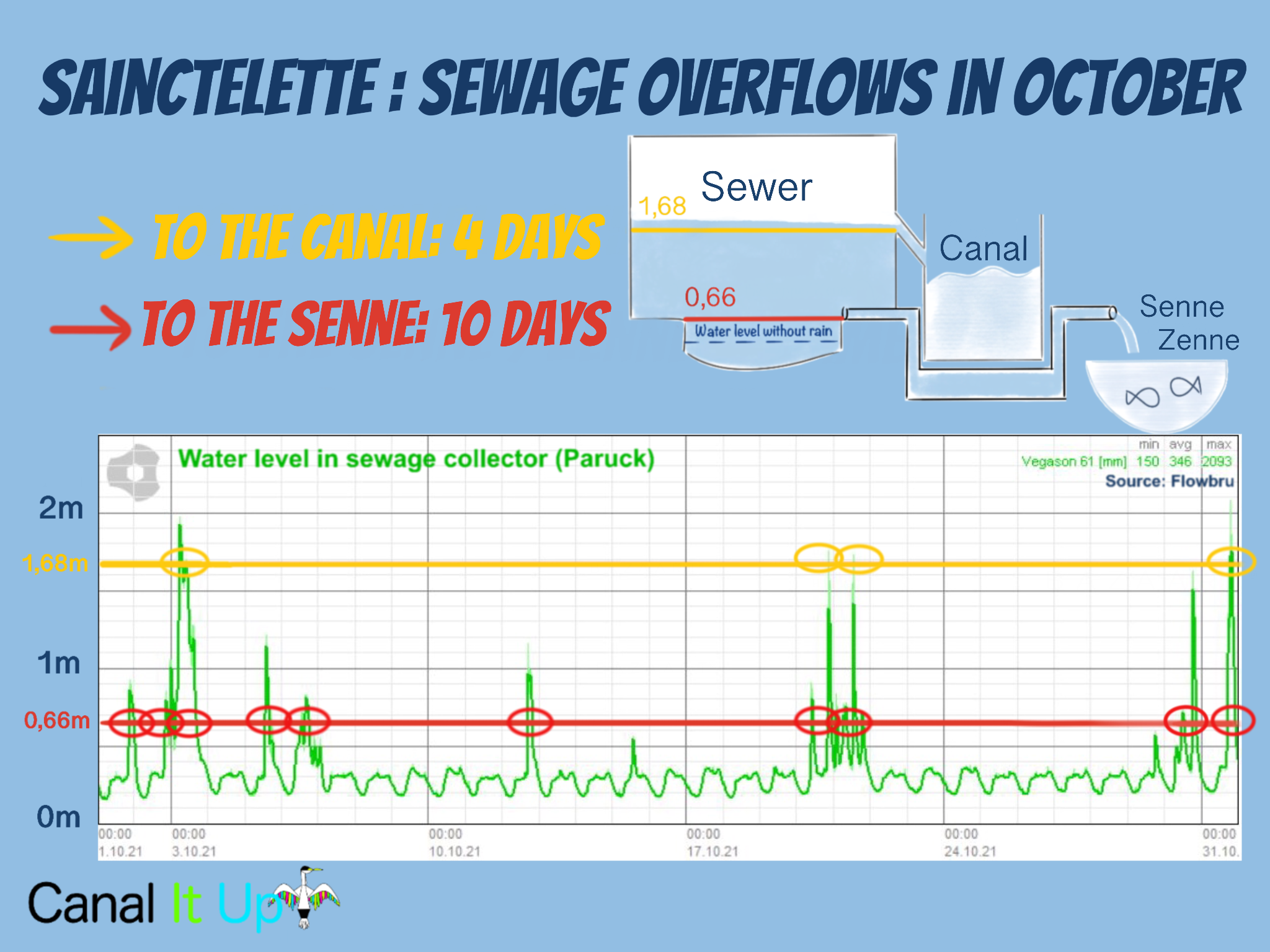

Number of overflows at Sainctelette:

2020:

In the canal: 21 days

In the Senne: 79 days

Precipitation: 753 mm

2021:

In the canal: 19 days

In the Senne: 100 days

Precipitation: 1058 mm

2022:

In the canal: 19 days

In the Senne: 80 days

Precipitation: 637 mm

2023:

In the canal: 32 days

In the Senne: 66 days

Precipitation: 1011 mm

2024:

In the canal: 24 days

In the Senne: 54 days

Precipitation: 1146 mm

You want to know more about the evolution of the overflows over the years? More information can be found at the end of this article.

Overflow events in January 2025

Sainctelette

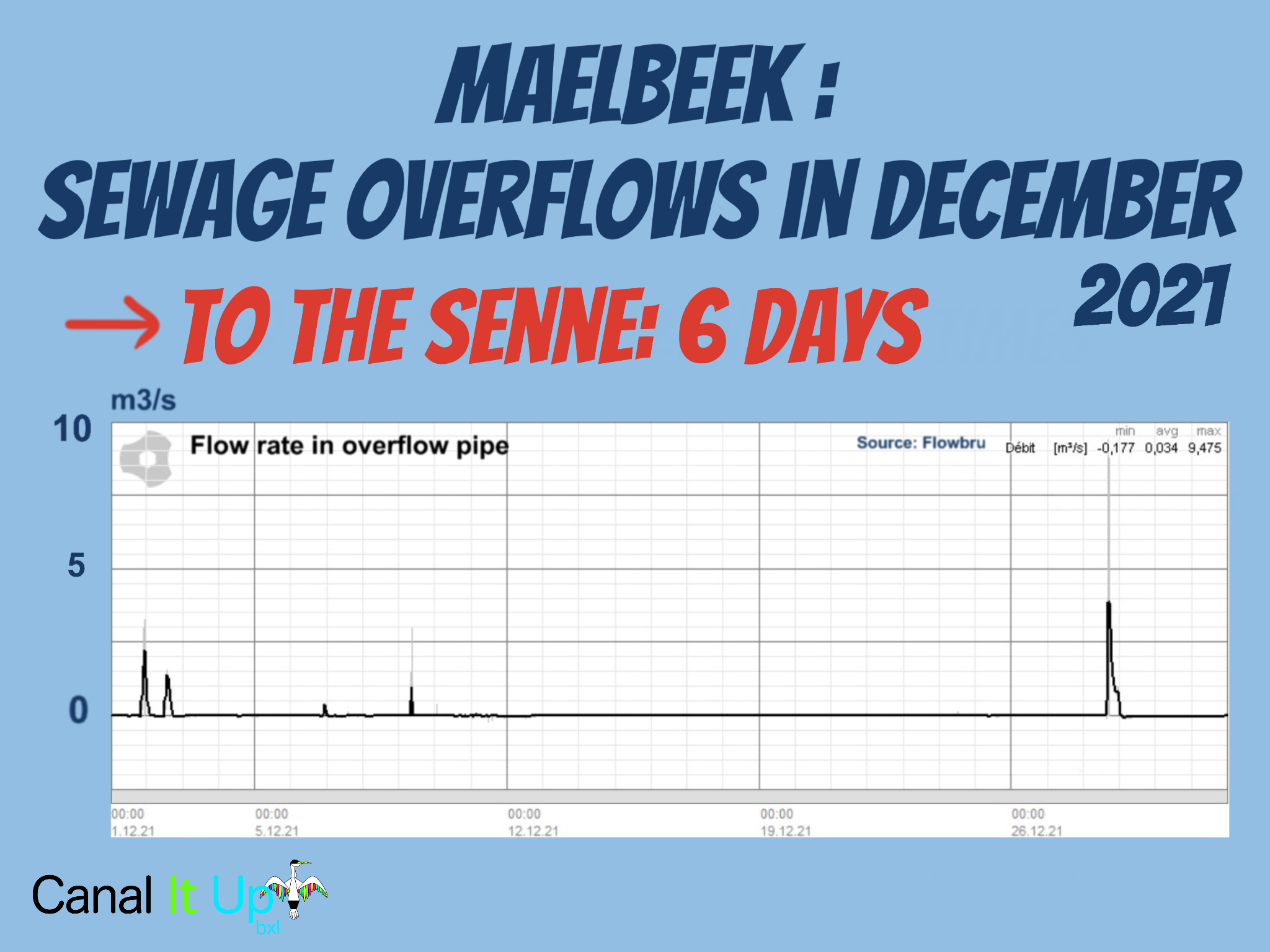

Maelbeek

The sewer overflows are a result of choices made in the past like the construction of a unitary sewer system. In this system, polluted water and rainwater enter the same sewer pipe. Another problematic choice was to connect all stormwater to this sewer system. All rainwater from roofs, streets and squares across the city flows directly into the sewer system. During the slightly more intense rainstorms, sewage water flows untreated into the Senne and the canal. This happens about 80 to 100 days a year and we are talking about a total yearly volume of 10 million m3 of sewage water discharged to the Senne and canal combined. To put this in perspective, Paris today discharges 2 million m3 of sewage per year to the Seine and Copenhagen 3 million m3 to its waterways and port. Both cities will soon reduce this to zero.

On top of the 10 million m3 discharged in Brussels, another 6 million m3 of sewage water is discharged into the Senne via the wastewater treatment plants. Before being discharged this sewage water is only slightly filtered flowing through the ‘filière d’eau de pluie’ when the treatment plants can’t handle all the water at once. This is therefore a large part of the volume of 125 million m3 of sewage water treated in Brussels every year. Connecting rainwater to the sewer system is not just a mistake of the past, it still happens today. Striking examples are the recently redesigned Rogier Square, Jourdan Square and Antwerp Gate. We already wrote an Open Letter in 2021 and an Open Video Letter in 2022 to the Brussels government to raise their attention and ask for more ambition to tackle the issue. The letters were signed by many other organisations. We also publish the number of sewer overflows every month and you can follow live on our homepage whether the sewers are overflowing or not.

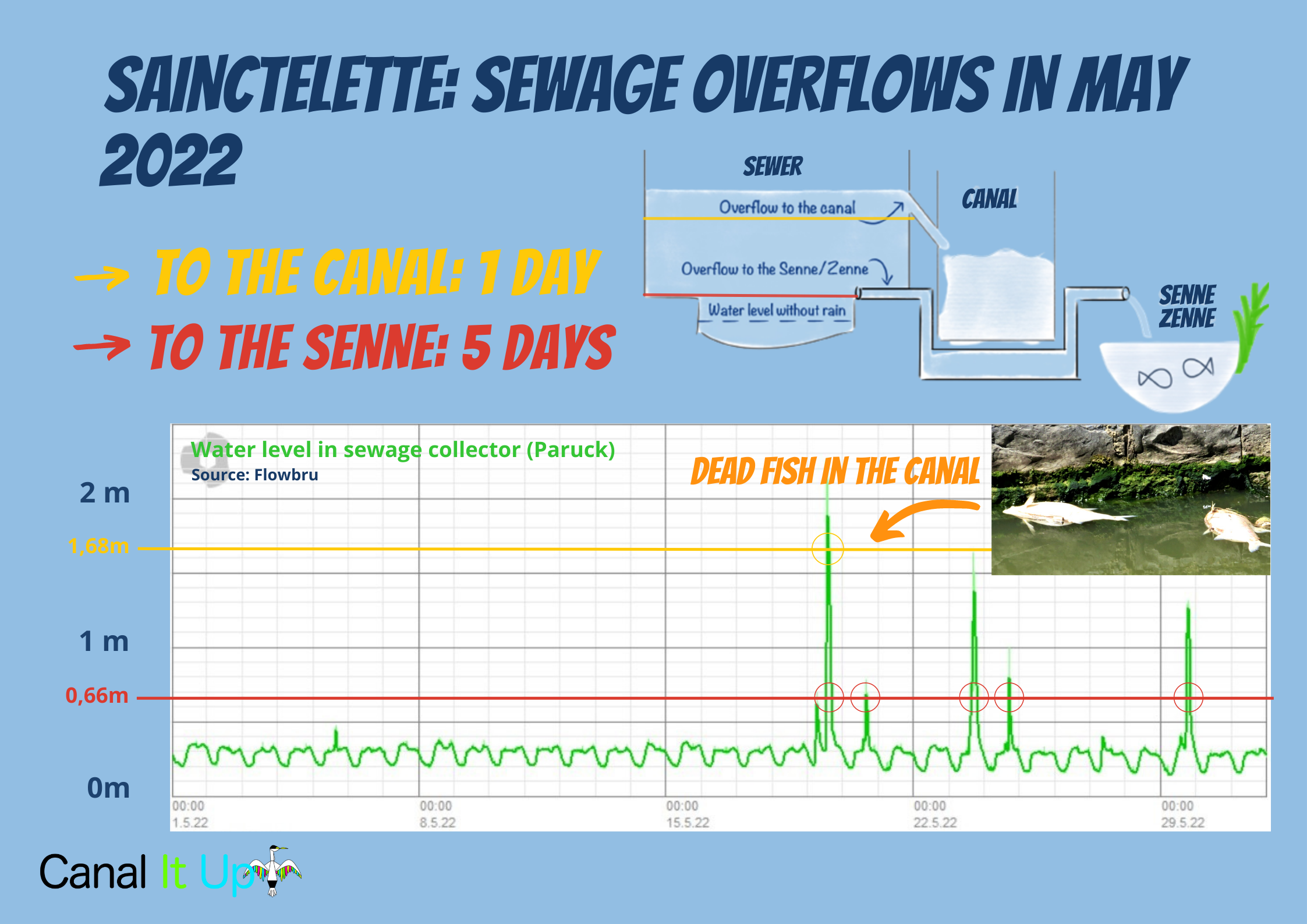

Video of sewage water overflowing into the canal

There are about 100 overflows in Brussels, three of which account for 75% of the volume of sewage water discharged. These are the overflows in Sainctelette (Paruck), Molenbeek and Maelbeek. Let’s take a closer look at the one at Sainctelette. When it rains, all the rainwater enters the sewer and the water level in the sewer rises. When the sewage reaches a certain level, it overflows into the Senne via the overflow and a siphon that passes underneath the canal. This siphon is the initial sewer pipe that connected the sewer system to the Senne before the two wastewater treatment plants were constructed in 2000 and 2007. Yes, until 2007, most of Brussels’ sewage water ran untreated to the river. When the water level in the sewers continues to rise, despite the discharge to the Senne, the second level of safety is reached and the water flows directly into the canal. And this happens without grating or any holding back of waste so everything, rats included, ends up in the canal along with the polluted water.

Diagram of the Sainctelette sewage overflow (Paruck).

What does an overflow look like from the inside?

Evolution of sewage overflows

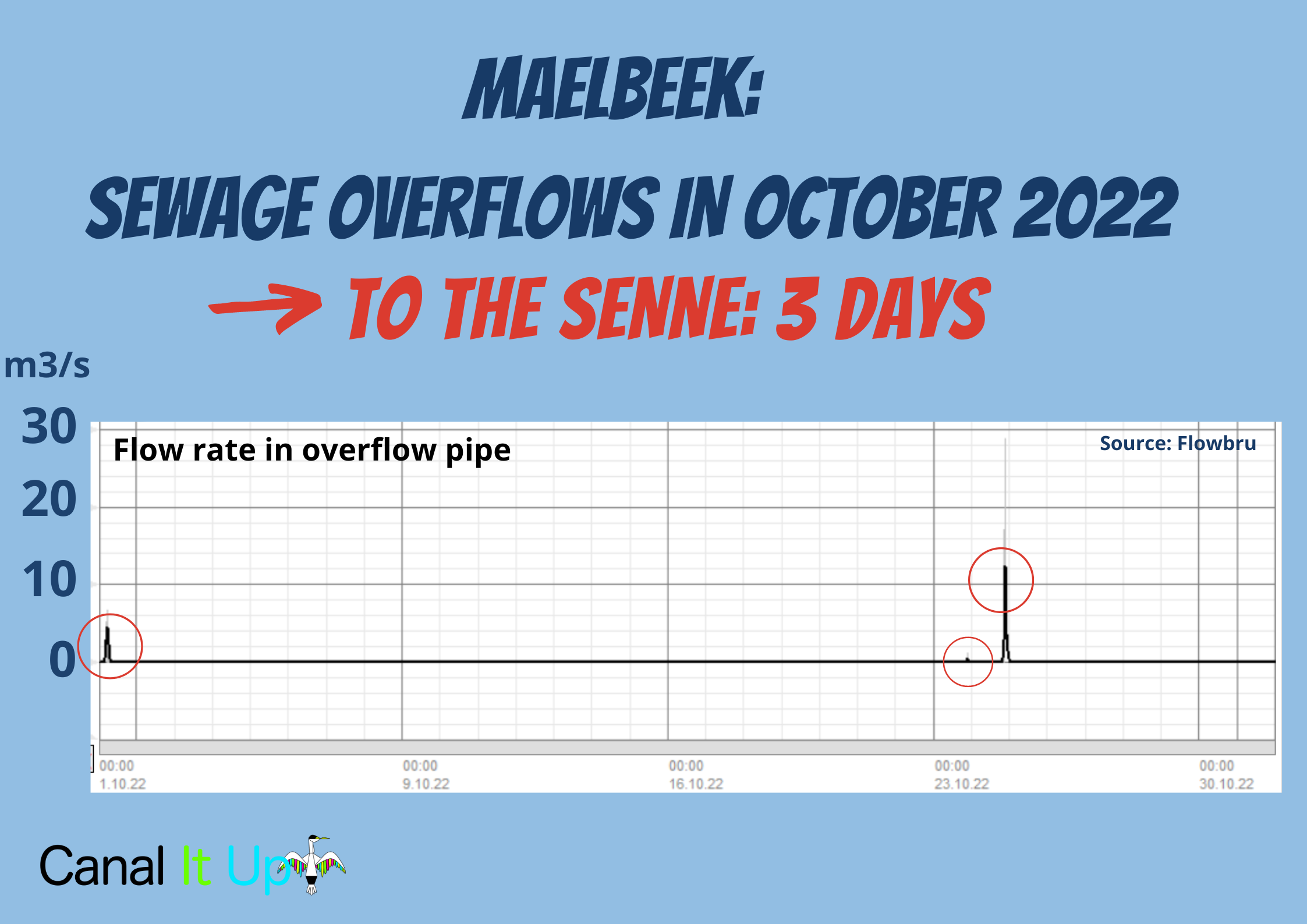

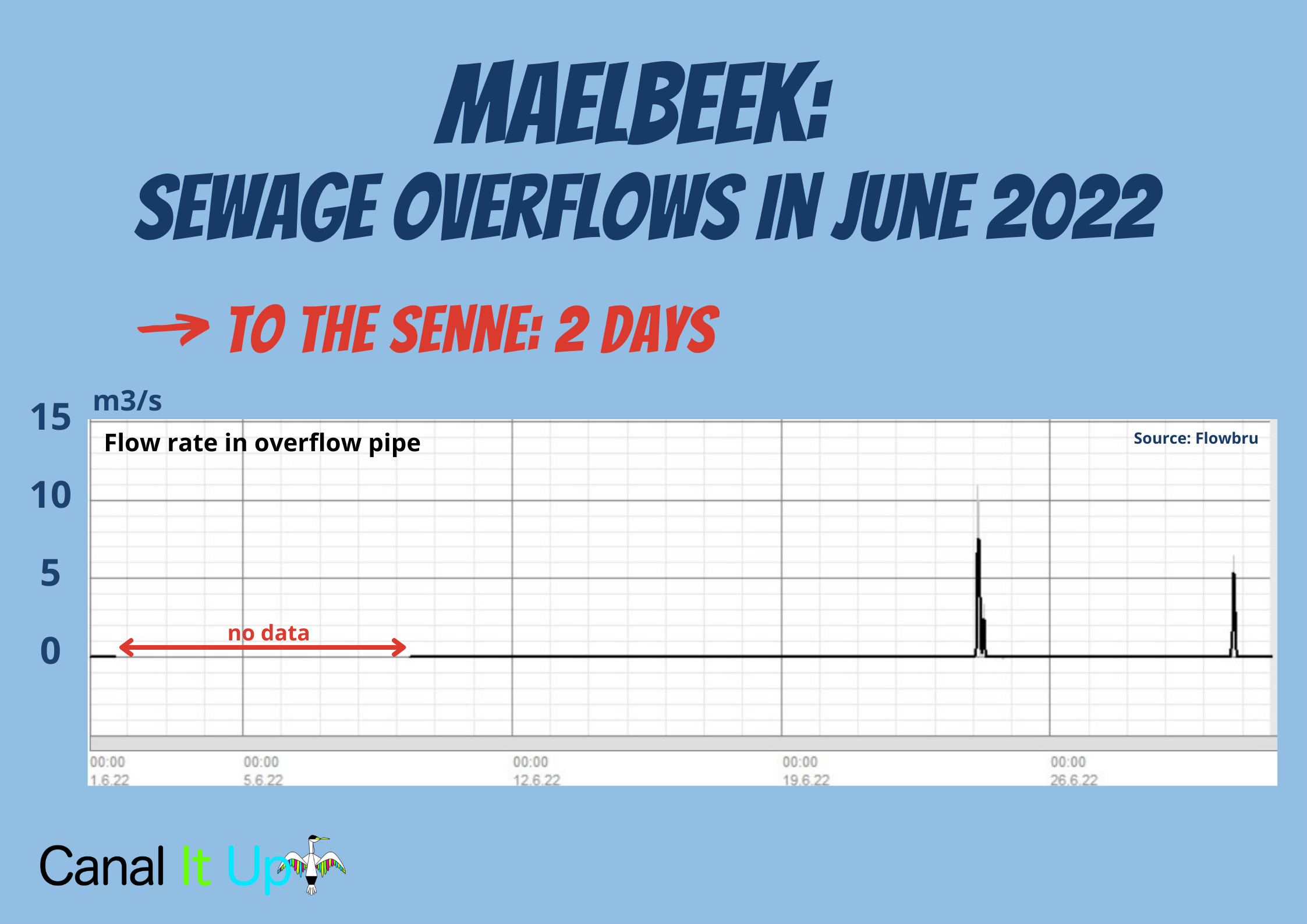

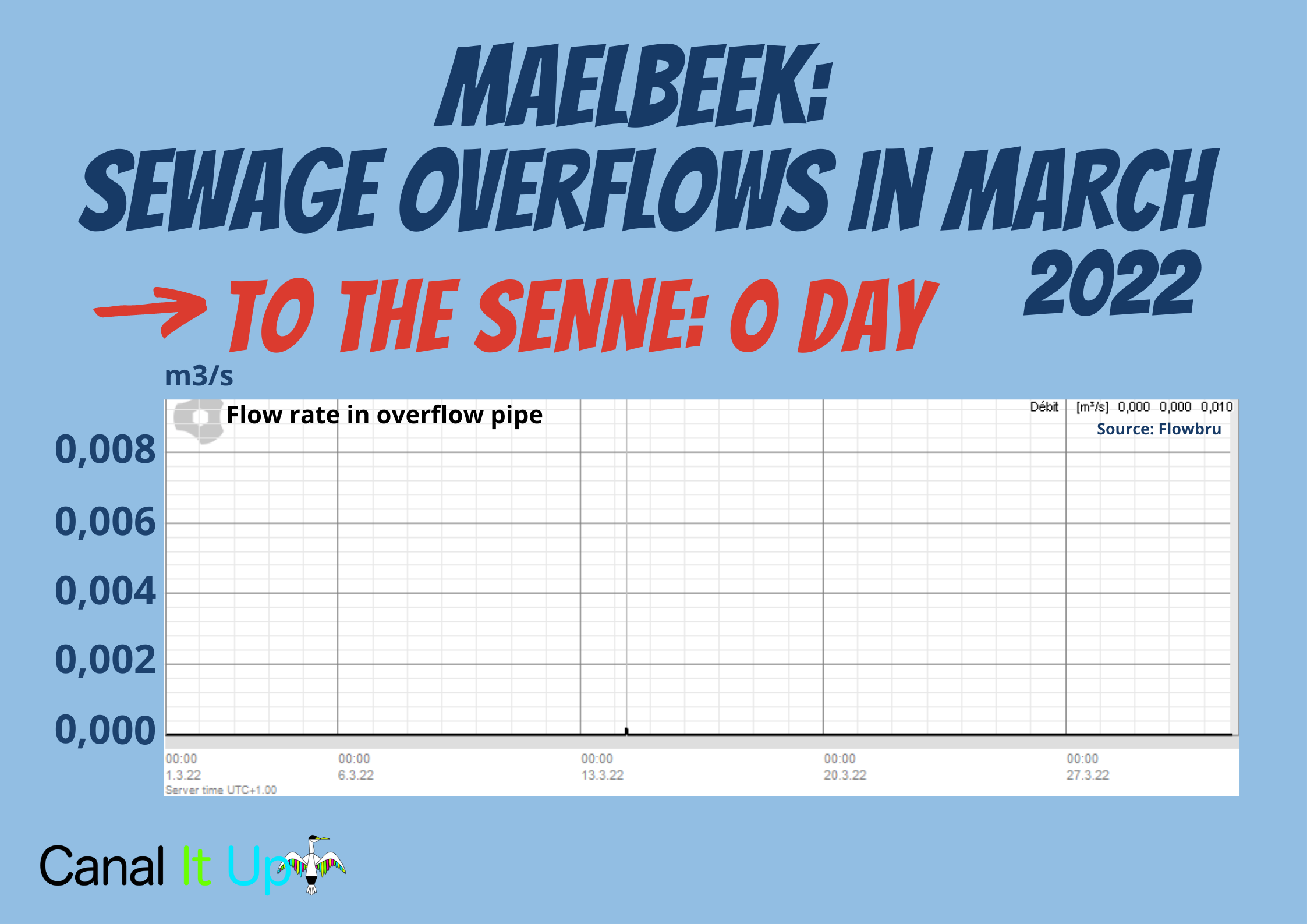

To map the number of overflows, we count the number of days the overflow operates at a significant flow rate. Thus, the overflow may discharge sewage water several times in 1 day but this is counted as 1 event. In 2022, +/-7 sewage discharges per month occurred to the Senne while a sewage overflow should normally only be used a few times per year. Sometimes these discharges continue for several hours.

Improvements to the overflow system can reduce the amount of overflows. For example in 2020 the sill of the Maelbeek overflow was increased which reduced the amount of overflows from 87 in 2019 to 33 in 2021. The Sainctelette overflow to the Senne has also been improved in 2022 and has drastically reduced the overflows as can be seen in the graph. These improvements keep more sewage water in the sewers and thus increases the volume that arrives at the sewage treatment plants which could lead to more sewage spills at the treatment plants itself. Today the plants already spill 6 million m3 of sewage water to the Senne every year.

The amount of overflows is also correlated to the amount and the distribution of the rain that has fallen that year. 2023 was a very wet year and thus the overflows to the canal increased. 2021 was also a very wet year but this didn’t affect the overflows to the canal which could be explained by the fact that it rained more but the rain was spread over more days and thus there were less extreme rain events that lead to an overflow.

What is the solution?

To answer this question, we organised a conference on 6 March 2023 with speakers from Copenhagen, Paris, London and Brussels. The problem of sewer overflows and flooding is not just a problem in Brussels. Paris for example set the goal of making the Seine swim-ready for the Olympics by 2024, several swimming disciplines will be held in the river. To that end, they are working hard today to reduce sewage discharges to zero by 2024 with a plan costing €1.2 billion. London today faces an annual overflow volume of 110 million m3 of water. For this, they are currently building a Super Sewer underneath the city that is due to be completed by 2025 and will cost €5 billion. The large sewer pipe will reduce the overflow volume by 95% to level of 5 million m3 a year. Copenhagen discharges 3 million m3 of sewage into the natural environment every year. But a bigger concern for them are floods like the 2011 flood that caused €1 billion in damage. For this, the city developed the Cloudburst Management Plan, an ambitious plan with a cost of €1.5 billion. 350 different projects throughout the city should protect it from floods and sewer overflows, creating new quality public spaces in the meantime.

What does a stormwater basin look like?

Unlike these foreign cities, Brussels does not yet set itself a specific target to reduce the 10 million m3 of overflows by a certain date. However, changes are being made at the overflow infrastructure, studies are being carried out to possibly use stormwater basins in a dynamic way and there are talks about integrated water management. There is also the Water Management Plan. A plan for which lots of people worked very hard with the goal to meet the European requirement for all waterways to achieve good chemical and ecological status by 2027. Brussels will probably not meet that by 2027 and neither by 2033, the next deadline. The plan proposes many measures without real specific projects in any street, square or stormwater basin. The plan is also drawn up by the regional actors, the municipalities with their own plans seem to be missing from it. A good example is the City of Brussels (Brussels, Laken, Neder-Over-Heembeek, Haren) that wants to disconnect 250,000 m2 of roofs from the sewer system by 2030. Given Brussels’ region complicated structure with 19 municipalities, it seems impossible to draw up one plan for the whole city. Meanwhile, climate change will bring more intense rainfall and the problem will only get worse.

Who will step up to unite the whole city behind a common ambitious goal?